On 19 October 2025, four thieves entered the Louvre’s Galerie d’Apollon through a second-floor window, smashed display cases and escaped with eight 19th-century royal jewels in under eight minutes. Prosecutors put the loss at €88 million, while stressing that the deeper damage is historical and symbolic. Empress Eugénie’s crown was dropped and later recovered outside, the remaining pieces are still missing as investigators review extensive CCTV and witness footage.

This is more than a security story. It cuts to why people visit museums at all: to stand with history, to feel the presence of time through singular objects that connect generations. When those objects vanish, the emotional charge that draws millions is jolted. The question that follows isn’t only how to protect treasures, but how to keep meaning alive. The Louvre’s leadership struck that balance, reopening quickly to reaffirm the museum’s bond with the public while acknowledging the wound.

The symbolism of what was taken

The stolen jewels formed a compact portrait of French imperial identity, tied to Empresses Marie-Louise and Eugénie and Queens Marie-Amélie and Hortense. Each piece compressed layers of personal and political life: statecraft, ritual, taste, affection. Their disappearance leaves visible gaps in how the Apollo Gallery narrates power, style and public memory. Photo essays and reporting helped a global audience feel those absences as a shared loss rather than a statistic.

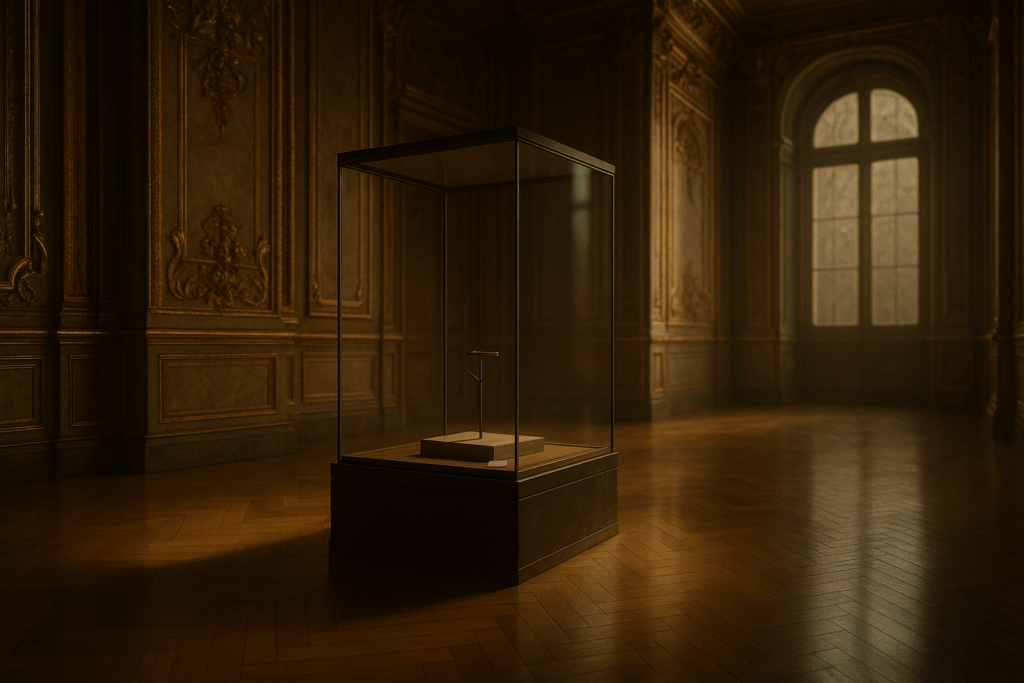

What absence teaches about presence

Immersion in a museum rests on three things: space, light and the charge of original objects. When one thread snaps, the others have to carry more weight. Dresden’s Green Vault learned this after its 2019 jewel heist, when recovered pieces returned in 2024, visitors encountered not only restored beauty but the endurance of care. In April 2024, Copenhagen’s 17th-century Old Stock Exchange (Børsen) burned during renovation and firefighters, staff and passersby formed human chains to rescue hundreds of works by Danish masters. Many suffered water damage, but the vast majority were saved and continue to be conserved and shown. Preservation isn’t just glass and alarms, it’s a living community willing to act in moments of crisis.

The Louvre now faces a similar test. Stolen royal jewels are rarely sold intact, heightening the fear that ensembles could be broken apart and their histories scattered. That uncertainty changes how audiences read the museum: absence becomes part of the story. When institutions share that vulnerability openly, they don’t erode authority, they deepen trust, reminding us that preservation is a continuous, collective act.

The museum as civic space

A heist becomes a civic drama. It draws in curators, conservators, ministers, journalists and visitors, all asking what these objects mean to us now. Within hours of the theft, media outlets mapped the route, identified the jewels and reconstructed the timeline. The discussion widened from “how could this happen?” to “what do we protect and why?” That public, imperfect conversation is part of what makes museums civic stages as much as cultural ones.

Presence after loss

When the Louvre reopened, it wasn’t just switching the lights back on. It was inviting visitors to witness continuity: to stand before what remains and acknowledge what’s gone. Museums matter because they model care, not closure. If the Apollo Gallery includes notes on the investigation, conservation updates or placeholders for the missing jewels, the experience will change, becoming quieter, heavier, but still profound because the story now includes fragility and resolve.

Where meaning goes next

The long-tail significance of this theft will likely unfold along three threads:

- Investigation and possible recovery. A return would echo Dresden’s journey from shock to renewal, a reminder that vigilance and patience can repair public memory.

- Interpretive response. From empty mounts to high-fidelity reconstructions and digital twins, museums can keep the objects’ lives present even when the materials are gone or off view.

- Public memory. Over time, the heist will enter the Louvre’s own mythology, much as the 1911 Mona Lisa theft did, shaping how future visitors “read” the Apollo Gallery.

The Louvre heist underscores a simple truth: museums are living institutions of stewardship and continuity. Their stories, like ours, sometimes include loss. What matters is how that loss becomes part of the way we keep remembering together.

Join the community dedicated to protecting our shared heritage. Support organizations that safeguard art, history, and memory for future generations.